As a schoolgirl, I was taught plenty about slavery and segregation in the US; I was taught that both were gross injustices, shameful times in our nation’s past. There was so much emphasis on the civil rights movement in our elementary school curriculum that whenever anyone asked me who my hero was, I always said “Rosa Parks.”

What I don’t remember ever being taught about, though, was lynching—at least not in very much detail. I didn’t learn about it in school, and I certainly didn’t learn about it in church. I was aware that in the Jim Crow South, white mobs sometimes brutalized black men and even killed them by hanging, but that was about the extent of my knowledge of lynching. I didn’t know how common and widespread it was. Nor that women and children were among the victims. Nor that burning and mutilation were almost always involved. Nor that lynchings were considered community-wide entertainments, replete with food vendors, souvenir salesmen, and free passes from school.

James H. Cone’s book The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Orbis, 2013) is both history lesson and sermon—a harrowing look at America’s national crime (as Ida B. Wells called it) and the ways it was (and was not) confronted as well as a brotherly rebuke of the white church’s silence on the issue and a proposal for how to move forward.

James H. Cone’s book The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Orbis, 2013) is both history lesson and sermon—a harrowing look at America’s national crime (as Ida B. Wells called it) and the ways it was (and was not) confronted as well as a brotherly rebuke of the white church’s silence on the issue and a proposal for how to move forward.

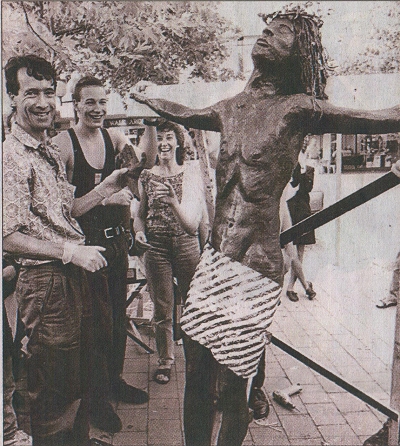

The two most representative and emotionally charged symbols of black experience in America, the cross and the lynching tree interpret each other, Cone says. The black community understood this; they embraced the cross of Christ in all its paradox, finding hope and empowerment in knowing that just as death did not determine Christ’s final meaning, so neither would lynching have the final word for them. But this symbolic link doesn’t serve only African Americans; people of all races would do well to ponder it and flesh it out, as it promotes a rich theology of suffering and a helpful base for race relations within the church. And in fact Cone doesn’t see such reflections as optional; he considers them necessary for the sake of the gospel:

The cross and the lynching tree are separated by nearly two thousand years. One is the universal symbol of the Christian faith; the other is the quintessential symbol of black oppression in America. Though both are symbols of death, one represents a message of hope and salvation, while the other signifies the negation of that message by white supremacy. Despite the obvious similarities between Jesus’ death on the cross and the death of thousands of black men and women strung up to die on a lamppost or tree, relatively few people, apart from the black poets, novelists, and other reality-seeing artists, have explored the symbolic connections. Yet, I believe this is the challenge we must face. What is at stake is the credibility and the promise of the Christian gospel and the hope that we may heal the wounds of racial violence that continue to divide our churches and our society. . . .

Until we can see the cross and the lynching tree together, until we can identify Christ with a “recrucified” black body hanging from a lynching tree, there can be no genuine understanding of Christian identity in America, and no deliverance from the brutal legacy of slavery and white supremacy. (xiii-xiv, xv)

Illustration by Charles Cullen. Frontispiece to Countee Cullen’s The Black Christ and Other Poems, 1929.

The Cross and the Lynching Tree integrates four different modes of writing—historical analysis, polemic, literary and visual art exegesis, and theological treatise—woven together into one vibrant, seamless cloth. I will examine each of these below. Continue reading