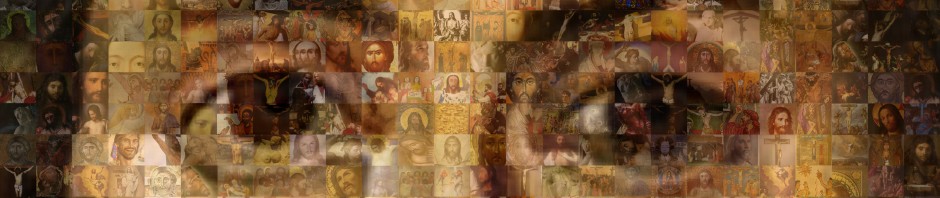

This is part 1 of a series on Christian art of the Pacific Northwest Coast.

In an address given at Martyrs’ Shrine in Huronia, Ontario, on September 15, 1984, Pope John Paul II said that “not only is Christianity relevant to the Indian peoples, but Christ, in the members of his body, is himself Indian.” This series is a celebration of the divine image-bearing First Nations peoples of coastal British Columbia, Alaska, Washington, and Oregon, and their art. Due to the nature of my blog, I have selected a handful of contemporary carvings and prints done in the traditional style that represent Jesus and/or his work. Each piece communicates powerfully who Jesus is in the eyes of its artist and is a reminder that even though historically God embodied himself in Jewish culture, his Spirit has taken residence in cultures all around the world.

First let me acquaint you with some of the names you’ll encounter. Within the Northwest Coast area, anthropologists have classified local groups into six large units speaking related languages: the Haida, Tsimshian, Kwakwakw’wakw (formerly Kwakuitl), Nuu-chah-nulth (formerly Nootka), Nuxalk (formerly Bella Coola), and Coast Salish. (Sometimes the latter two are combined under the name “Salishan,” and the first two are combined along with Tlingit and called the “Northern cultures.”) Within each of these broad classifications, however, are many distinct tribes that have formed their own nations with their own social structures and traditions, and within each tribe there are two or more clans (some of the most common are the Raven, Eagle, Bear, Killer Whale, and Wolf clans), based on descent from a common (nonhuman) ancestor. Clan crests are what make up much of Northwest Coast art.

For a more detailed map and pronunciation guide of First Nations peoples in the Northwest Coast area, visit the British Columbian government website.

Totem poles

The Northwest Coast is the region where totem poles originated. Made of red cedar and sometimes painted, sometimes not, totem poles were carved to commemorate a family clan by recounting its history, qualities, privileges, and beliefs. Most commonly they tell of a clan’s mythological beginnings or of some legendary event from the clan’s past.

Although most people are familiar with the freestanding ones, totem poles were also used as interior house posts or house frontal poles.

Interior of Chief Klart-Reech’s House (Whale House at Klukwan), Chilkat, Alaska. Photo: Alaska’s State Library (Winter & Pond), 1895.

This house portal pole in Alert Bay was carved by Yuxwayu in the second half of the nineteenth century as a memorial to Chief Wa’kas. The Raven’s beak opens to form a doorway. (The upper part is the prow of a canoe.)

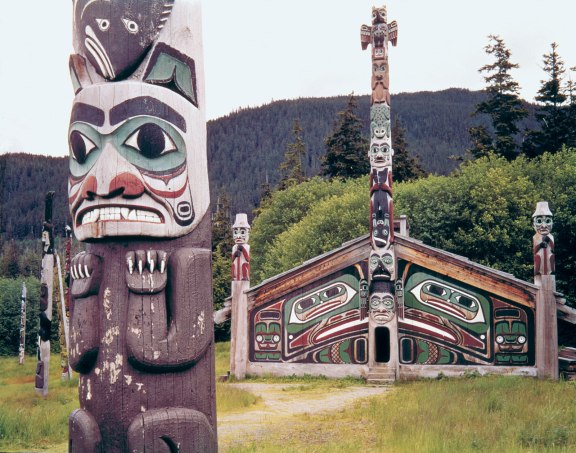

A Tlingit community house and totem poles are preserved in Totem Bight State Historical Park in Ketchikan, Alaska.

Potlatches

Totem poles were raised at potlatches, lavish winter gift-giving festivals in which a family would showcase its wealth by distributing it among guests. Clothing, glasses, canoes, furniture, pool tables, jewelry, violins, guitars—these and more were given away by the host chief so as to establish his high status in the community and his reputation as a generous gift-giver. Potlatches provided the occasion for the creation not only of totem poles but also of feast dishes, utensils, masks, and rattles—other characteristic artifacts of Northwest Coast cultures.

Dancers posing in potlatch regalia, Fort Rupert, 1914. Photo: Edward S. Curtis, in the collection of the Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia.

Because potlatches included song and dance rituals that they did not understand, the Canadian government issued a ban on potlatches in 1884. This drove potlatching underground. The ban was repealed in 1951, which gave way to a revival of Northwest Coast art that is continuing to this day.

Below is a short video clip that documents a Kwakwaka’wakw potlatch given by Chief Amos Dawson in what I would guess is the late 1960s.

Several tribes still hold potlatches today.

Common misconceptions

According to Aaron Glass and Aldona Jonaitis, authors of The Totem Pole: An Intercultural History, the word “totem pole” is a misnomer because “the social and spiritual structures of Northwest Coast peoples do not conform to classic anthropological models of totemism.” Although there is disagreement on the precise meaning of the term “totem,” one common definition is an animal believed by a particular group to have religious significance and which they therefore treat with special reverence (no hunting or eating it) and look to for protection. None of this is true of the Northwest Coast peoples.

Contrary to the claims of nineteenth-century Christian missionaries, totem poles are not and never were worshiped as idols or sacred objects. In the book Haida Totems in Wood and Argillite, S. William Gunn wrote, “A totem figure will be better understood if it is looked upon as the equivalent of a European coat of arms; it is respected but never worshipped, having, like an emblem of heraldry, meaning but no religious significance.” Nor were totem poles ever used as talismans to ward off evil. No spirits were said to reside in them.

If, however, we take the word “totem” to mean merely a heraldic emblem adopted by a clan, as its etymology suggests (the word is derived from the Ojibwe word odoodem, meaning “his kinship group”), then yes, the erected poles in the Pacific Northwest do depict such totems. More properly, though, they are called “crests.”

So what kind of relationship exists between a clan and the figure on its crest? How are they chosen? First off, each clan has more than one crest. The beings represented are those from mythical times who became, or were encountered by, the ancestors of a lineage. By virtue of this descent or encounter, that group earns the right to depict that being on its crest. Each tribe has its own mythologies associated with the beings, though there is quite a bit of overlap.

One last misconception regarding totem poles is that the vertical arrangement of figures represents an order of importance—that the higher figures are the most significant. This misconception is so prevalent that it has given rise to the expression “low man on the totem pole.” This interpretation may be true for some totem poles, but it is not a rule; the arrangement is entirely up to the artist. Some poles follow a reverse hierarchy, with the most important figure on the bottom where people can view it at eye level, and still other artists choose to emphasize a figure in the center of the pole.

Impact of European contact

The first European ships arrived on the Northwest shores in the 1770s—first the Spanish, then the British, French, and Russian, the latter forming permanent settlements in Tlingit territory by the end of the century. These newcomers bought lots of sea otter furs from the Native Americans, which greatly prospered both parties. By 1824, permanent land-based trading posts had been established.

After this convenience was in place, Protestant and Catholic missionaries moved in. In contrast to the fur traders and maritime explorers, who reacted favorably to the art they encountered, the missionaries were opposed to totem poles because they mistook them for idols. As a result, writes Hilary Stewart, totem poles were felled or sold; some were even cut up for firewood (20).

In 1857 the British population on the coast exploded when gold was discovered along the Fraser River. Families came to settle there permanently, bringing with them smallpox. This disease swept quickly through the region, reducing the Northwest Indian population by about a third.

You would think that this period of increasing oppression by whites and population decimation would have had a negative, if not fatal, impact on the region’s art, but surprisingly, the opposite was true. Aldona Jonaitis writes that when certain elite families died out, they left power vacuums in their villages. Other families had to prove their worthiness for the vacant positions of village chiefs, which meant more competitive potlatches, which required the creation of an even greater number of more splendid artworks—the patronage of which was made possible by the wealth accrued from fur trading. Ironically, Jonaitis says, “Northwest Coast artwork flourished as never before, as taller totem poles, more impressive houses, and more dazzling costumes had to be made in order to satisfy the needs of the remaining Indians who wished to use their art to convince the world of their prestige and importance” (50).

Another factor of this artistic flourishing was the introduction of better tools and materials. Due to trade, carvers now had at their disposal metal axes, adzes, and chisels, which allowed for more complex relief sculpture, as well as trade pigments, such as the rich vermillion from China, which resulted in much brighter paintings on the wood sculptures.

The most photographed totem poles in the world are the nine at Brockton Point in Vancouver’s Stanley Park. (This photo from 2008 does not include the park’s most recent acquisition, a pole by Squamish Nation artist Robert Yelton in 2009.) All but Nos. 3, 5, and 8 are done in the Kwakwaka’wakw style. The artists and dates of execution are: (1) Oscar Maltipi, 1968, (2) Ellen Neel, 1955, (3) Norman Tait, 1987, Nisga’a, (4) Doug Cranmer, 1987 (replica of ca. 1880s original by Yuxwayu), (5) Art Thompson and Tim Paul, 1988, Nuu-chah-nulth, (6) Tony Hunt, 1988 (replica of early 1900s original by Charlie James), (7) Wayne Alfred and Beau Dick, 1991, and (8) Bill Reid, 1964, Haida.

Are totem poles still being carved today?

Yes, but the context of their creation and raising is in many cases quite different from what it used to be. The Golden Age of totem poles was the mid-nineteenth century, a time in which some native villages had as many as seventy poles erected. As noted earlier, chiefs competed with one another to erect the most impressive poles, and the occasion for their raising was almost always a potlatch. Today most commissions come from non-natives for display in or outside museums, parks, or government buildings. The raising ceremonies are thus adapted to a different audience.

This video shows the preparation and unveiling of a totem pole by Tsimshian artist David Boxley at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC, just last year.

Because of the nature of that space, the museum staff was responsible for the pole’s raising, but many outdoor raisings involve the local community pulling on ropes from five or more directions. See this collection of stills with spliced-in audio and notes from the raising of the Centennial totem pole in Sitka National Historical Park on May 15, 2011, carved by Sitka artist Tommy Joseph. Notice the commemorative references on the pole to the park’s Russian history.

___________________

The purpose of this introductory post is to provide you with sufficient background information on the history and culture of the Northwest Coast peoples so that you can better connect to the artworks presented in subsequent parts of the series. Lest you feel disappointed that this post has nothing do with its title, check back for part 2 sometime this weekend.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Glass, Aaron and Aldona Jonaitis. “The Totem Pole: Material Transformation of a Cultural Icon.” Material World. October 17, 2010. <http://www.materialworldblog.com/2010/10/the-totem-pole-material-transformation-of-a-cultural-icon/>

Halpin, Marjorie M. Totem Poles: An Illustrated Guide. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 1981.

Jonaitis, Aldona. From the Land of the Totem Poles: The Northwest Coast Indian Art Collection at the American Museum of Natural History. Vancouver/Washington, DC: Douglas & McIntyre/American Museum of Natural History, 1988.

Stewart, Hilary. Looking at Totem Poles. Vancouver/Seattle: Douglas & McIntyre/University of Washington, 1993.

Stewart, Hilary. Looking at Indian Art of the Northwest Coast. Vancouver/Seattle: Douglas & McIntyre/University of Washington, 1979.

Pingback: Jesus as Thunderbird: A Crucifix-Totem Pole by Stanley Peters | The Jesus Question

Pingback: Christmas and Easter Totem Poles by David K. Fison | The Jesus Question

Pingback: Jesus as Sun-Face: A Panel Carving by Don Froese | The Jesus Question

Pingback: Jesus as Chief: “Baptism Mural” by Tony Hunt | The Jesus Question

Pingback: One with Christ: Prints by Roy Henry Vickers | The Jesus Question

Pingback: Celebrating Christ in All Seasons: Liturgical Bentwood Boxes by Charles W. Elliott | The Jesus Question

Pingback: ArtWay Visual Meditation ~ January 25, 2015 | Global Light Minds

Martyr Shrine is not in British Columbia, but Ontario. St, Marie Among the Hurons is north of Toronto in the province of Ontario.

Love this wonderful post and discovery of North West Coast history and tradition.

Thank you.

Thank you for the correction; I updated the content above to reflect it.