While visiting Oxford in April, I had the pleasure of meeting artist Nicholas Mynheer and, what’s more, of having him talk me through some of his works on location. One of my favorites was the glass screen he designed for Saint Nicholas’s Church in nearby Islip, installed in 2011.

Sandblasted glass screen at the west end of the Church of St. Nicholas, Islip, Oxfordshire, England. Designed by Nicholas Mynheer and made by Davia Walmsley of Daedalian Glass, 2011.

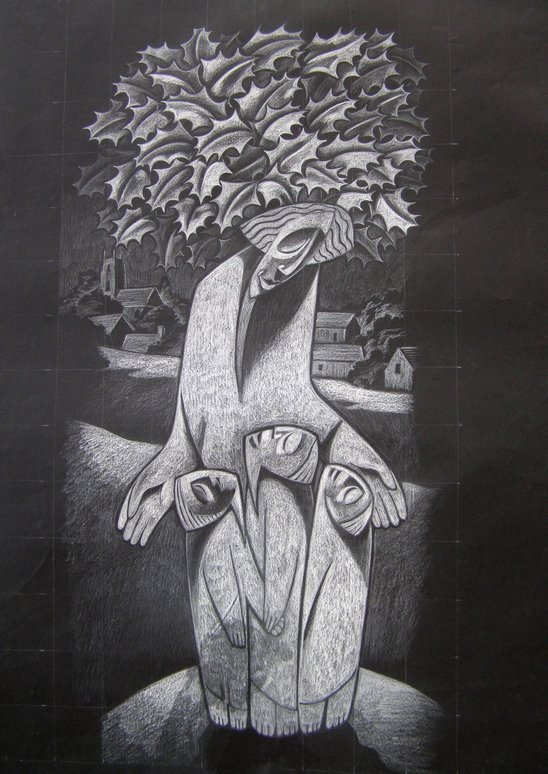

The screen depicts scenes from the life of St. Nicholas, a fourth-century bishop from Asia Minor and the prototype for Santa Claus, and the life of St. Edward the Confessor, who was born in Islip and reigned as King of England from 1042 to 1066. Though separated by seven centuries and a continent, the lives of these two men mirror each other in several ways—because they both mirror Christ. Key episodes unfold in parallel up each side of the screen, with the blessing hands of God the Father at the top, and the blessing hands of Christ at the base, behind whom lies the village of Islip.

In the bottom two corners are depicted acts of giving: St. Nicholas gives bags of gold to three young women to save them from a life of prostitution, and St. Edward gives a beggar his gold ring. Each saint extends his arm downward in a gesture of mercy. Theirs is a piety expressed by concern for the poor.

(Related post: “The Real Saint Nick”)

Upward-reaching gestures mark and balance the middle of the screen: St. Nicholas intercedes for a group of sailors during a storm, saving them from death at sea, and St. Edward carries a crippled man on his back to the chapel altar, where he receives miraculous healing. In both stories there is a feeling of helplessness, but the saints show confidence in God, from whom comes deliverance, whether from storm or disability. The raised arms of Nicholas and the lame man point us to this saving God.

At the top St. Nicholas, wearing his bishop’s mitre, holds a scale model of St. Nicholas’s Church, while St. Edward, in royal crown, holds a model of Westminster Abbey, which he had rebuilt back when it was called St. Peter’s Abbey and where his body is buried today. The center of this panel is left undecorated so that it can more clearly reflect the stained glass window opposite it at the east end of the church.

At the bottom center—which is where my eyes started and kept returning—Jesus looks down with joy on three little children, who have gathered in front of him. However, this setup also recalls the most famous miracle story associated with St. Nicholas: his raising three boys from the dead. Notice, Mynheer said, how their feet do not touch the ground. Their resurrection here functions in a double sense: as an allusion to the St. Nicholas story but also as a reminder to worshipers of the resurrection they’ve experienced personally in Christ. When we approach him with the faith of a child—with pure, eager, and trusting hearts—he gives us new life. This is Christ’s supreme giving act, which inspires the two that flank him.

But this gift of life came at the expense of his own, of which the holly tree behind him serves as a reminder. Holly has long been a symbol of Christ’s passion. According to tradition, Christ’s cross was made from a holly tree and his crown of thorns from its branches. A popular medieval Christmas carol called “The Holly and the Ivy” bears out the symbolism of blossom, berry, prickle, and bark, linking each to Christ. In the context of St. Edward, the tree takes on an additional layer of meaning as a reference to St. Edward’s deathbed prophecy regarding the English dynasty, in which he warned that the “green tree” would soon be cut away from its trunk and moved three acres away but would eventually return and bring forth leaves and fruit once again. (The prophecy is traditionally interpreted as the marriage of the Saxon and Norman royal lines under Henry II, following the reigns of the three Norman kings: William I, William II, and Henry I.) The holly tree therefore harks back to both religious and national history, to events that led to great flourishing.

This portion of the screen actually forms a set of double doors, behind which is a staircase leading up to the children’s church room, a small carpeted area with a table-and-bench set and a shelf of books and toys. Situated opposite the altar on a second story, this room provides a great view of the sanctuary, a chance for the children to observe the worship service through the St. Nicholas-St. Edward screen as they play and learn about Christ in their own ways.

Mynheer said that when he visited one Sunday, it was neat to see the children dismissed through the doors where Christ gathers the children together and blesses them, and where St. Nicholas, the patron saint of children, is also honored. Mynheer also mentioned having attended a wedding in the church once and being delighted to see the doors used as a part of the ceremony: for the entry of the bride. All dressed in white, she passed under God’s blessing and between the giving hands of two saints, toward the altar where she likewise would participate in an act of giving: of herself to her new husband, through the vows of marriage.

The main entrance to the church is to the left of the screen on the south side, so parishioners do not frequently pass through the screen (with the exception of the parish children), but they do frequently pass by it. In lifting up the object of our faith—God in Christ—and two of its heroes, it provides an important means of contemplation. As I stood before it, having heard Mynheer explain the saintly deeds that inspired him in his design, I prayed for a heart of mercy like Christ, St. Nicholas, and St. Edward; for eyes that see the needs around me; for hands that are not stingy; for strength to carry the weak; and for boldness to call on God’s miraculous intervention in situations that are more than I can handle.

May all God’s people be agents of resurrection and generosity in the world!

With the exception of the preparatory sketch, all photos in this post are © 2013 by Victoria Emily Jones. You are welcome to use them for noncommercial purposes, but if you do, I ask that you please cite this page as the source.

Pingback: Nicholas Mynheer’s Glass Screen at Islip | The Jesus Question

Pingback: Roundup: Liturgical video installation; Mynheer profile; SYTYCD; natural-world mystic poetry; lament song – Art & Theology

Thank you for this post, I’m linking it to my Blog the Church Explorer where I am writing about the interior of this church. https://thechurchexporer.blogspot.com/2021/07/st-mary-virgin-charlton-on-otmoor.html