Last week I posted photos of some of the Yoruba Christian art housed at the SMA African Art Museum. Now I’d like to share a few from the museum’s Ethiopian collection.

Christianity has existed in Ethiopia since the first century AD. The Ethiopian Kingdom of Aksum adopted it as its official state religion around 324 at the decree of King Ezana, making Ethiopia the only country in sub-Saharan Africa to have accepted the Bible before the arrival of Western missionaries.

Ever since its founding by Frumentius, the Syrian traveler who converted King Ezana, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church has played a prominent role in the cultural development of the country. Ethiopian literature and art, for example, were born in the Church and traditionally are religious in content.

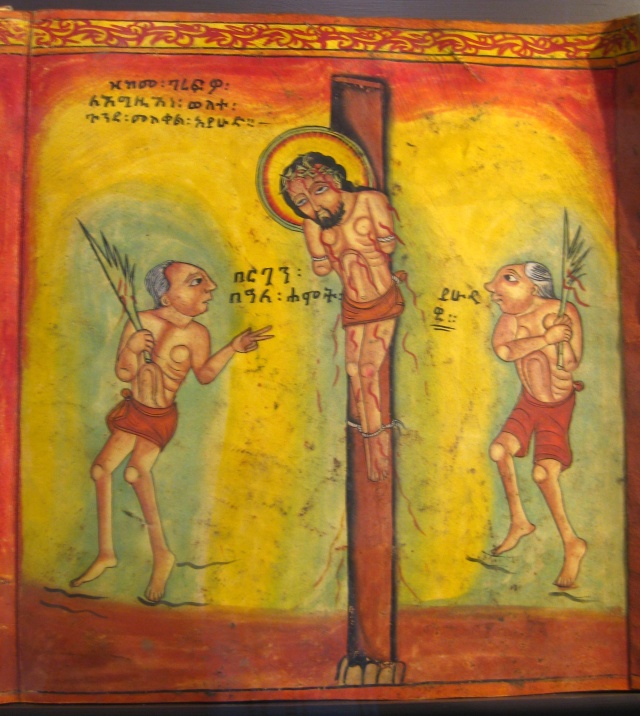

Below are a few detail photos of a twelve-panel folding icon, or chain manuscript, created around 1900. This form, called a sensul, first appeared in Ethiopia in the sixteenth century. It involves a cycle of pictures painted on a single strip of parchment, which can be folded for portability, for use either in processions or in private devotions.

The inscriptions, as in almost all Ethiopian Christian art, are in Ge’ez, the ancient Ethiopian ecclesiastical language. Like Latin in the Roman Catholic Church, Ge’ez is no longer widely spoken but continues to be used for scripture, prayers, hymns, and devotional literature.

This image shows Jesus tied to a wooden stake, being whipped by two servants of Pontius Pilate.

The adjacent image shows Jesus on the cross, flanked by Mary on his right side and John on his left. In terms of composition and motifs, the image is very reminiscent of Crucifixion paintings from the Byzantine and Italian Renaissance traditions. But in terms of color—the bright yellow glow against a red background, for example—it is wholly unique. Another unique feature is the purple band streaked with white squiggles (falling stars?) at the top to delineate the sky. (In Western paintings, the sky realm is usually not distinct from that of earth.)

The three motifs present here, as I mentioned, are also common in Western art. They point to symbolic significances:

- The sun and the moon above the cross represent the cosmic significance of the Crucifixion event. All of nature watches on as their king, Jesus, suffers, and they bow their heads in grief. (Artists typically give them faces, as here, to emphasize this personified aspect.)

- The skull and crossbones at the foot of the cross are meant to recall the death of Adam and, by extension, the death sentence given to all mankind. The Bible tells us that Jesus was crucified on a hill called Golgotha, which means “Place of the Skull.” According to legend, Adam was buried under this hill. By including his bones at the scene, the artist reminds us that Christ’s death is for the life and redemption of fallen man.

- The angels who catch Christ’s blood in chalices emphasize the sacramental significance of the Crucifixion, for it is this blood that we drink in the celebration of the Eucharist; we take him into ourselves as we remember his sacrifice.

The last panel of this folding manuscript contains three registers, which show the dead Christ (1) being held by his mother (a subject traditionally referred to as the Pietà), (2) being transported to the tomb by Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, and (3) being wrapped for burial. I love the conception of angels shown here: bodiless expanses of wings, with heads peeking out. I also appreciate the palpable emotion expressed in the tear-streaked faces of those who attend to the corpse of Christ. He had been their friend, teacher, savior—and now he was gone. (Until two days later, that is.)

For more online Ethiopian art viewing, here are a few links I recommend:

- Betsy Porter’s Ethiopia webpage

- Special Collections of the University of St. Andrews, Scotland: This link shows illuminations from an eighteenth-century Ethiopian psalter.

- Walters Art Museum Ms 36.10: Here’s another sensul, this one from the seventeenth century. (You can also select a fully open view or an interactive book-scrolling view.)

- Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection

- BibliOdyssey roundup

If you know of any others, please add them to the comments section!